The Zionist Movement’s fundamental position, whereby the Golan is part of the future Jewish State, remained steadfast and unwavering, even after the British-French accords were reached during the 1920s that excluded the territories of the Golan from the scope of British control.

Jewish communities in the Golan and the Hauran in the modern era

Upon its founding at the end of the 19th century, the Zionist Movement considered the Golan Heights part of the landscape of the Jewish people’s historic homeland, adopting Herzl’s vision, who considered the Golan an integral part of the Jewish sovereign territory being reclaimed in the Land of Israel.

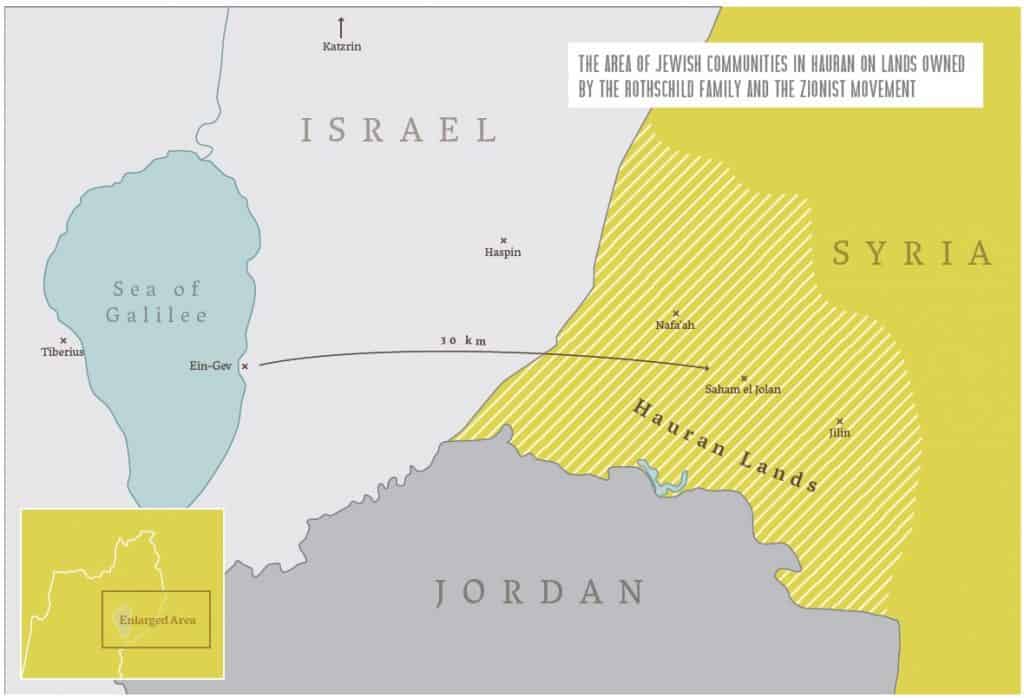

In 1883 and 1884, the communities of Yesod Hama’ala and Metula were founded in proximity to the Golan and heralded the resumption of Jewish life in the region. The settlement undertaking in the Golan and in the Hauran region – a region bordered in the north by the town of Quneitra, in the south by the Yarmouk River, in the east by Jabal al-Druze (inclusively) and in the west by the Golan – began in 1891, with Baron de Rothschild’s purchase of 150 square kilometers of land in the region where the villages of Sahem al-Jawlan, Jileen and Nafa’a are currently located, about thirty kilometers east of Ein-Gev. Baron de Rothschild’s purchase of the land was lawfully transacted and is backed by kushans, the title deeds to the land issued by the Ottoman regime.

In 1895, the first settlers occupied the land and began constructing Jewish communities in the Hauran region, including Zichron Menachem, Nahalat Moshe, Tifferet Binyamin, Achvat Yisrael and Beit Ikar. Already at the outset, the Jewish settlement enterprise in the Hauran faced considerable difficulties, which included attacks by local Arabs, a hostile attitude from the Ottoman authorities and isolation and severance from other Jewish communities. The gravity of the situation of the Jewish communities in the Hauran, which, at its peak, reached about 72 families in nine outposts, began showing its effects when Jews began gradually abandoning the region. In 1901, most of the Jews were forced to leave the Hauran.

In 1895, the first settlers occupied the land and began constructing Jewish communities in the Hauran region, including Zichron Menachem, Nahalat Moshe, Tifferet Binyamin, Achvat Yisrael and Beit Ikar. Already at the outset, the Jewish settlement enterprise in the Hauran faced considerable difficulties, which included attacks by local Arabs, a hostile attitude from the Ottoman authorities and isolation and severance from other Jewish communities. The gravity of the situation of the Jewish communities in the Hauran, which, at its peak, reached about 72 families in nine outposts, began showing its effects when Jews began gradually abandoning the region. In 1901, most of the Jews were forced to leave the Hauran.

The Jewish settlement on the Baron’s lands in the Hauran was not the only settlement effort during this period. In 1886, the Bnei Yehuda community was founded east of the Sea of Galilee, on land purchased by the Bnei Yehuda Society, whose members included Jews from Safad and from Tiberias.

The struggle for borders in the 20th century

As the years passed, notwithstanding the events of World War I and the departure of the Jews from the region at the end of the 19th century, the lands in the Hauran remained under the ownership of Baron de Rothschild and the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association (PICA). The lands were worked, inter alia, by virtue of lease agreements with local Arabs, and taxes for them were duly paid to the French Mandate.

Prior to the end of World War I, the Zionist Movement began issuing a public demand to include in the Jewish State to be established in the Land of Israel the Lebanese Beqaa Valley lying between Mount Lebanon and Mount Hermon, as well as the Golan Heights, the Hauran and the Yarmouk Valley. The proposal to include the Golan within the borders of the Land of Israel derived from settlement rationale and agricultural requirements that were necessary, inter alia, to ensure that sources of water were included within the borders of Israel – the sources of the Jordan River, the lower section of the Litani River, Mount Hermon, the Yarmouk River and the Zarka River. The need to ensure the supply of water to the state-in-the-making was one of the key rationale for the Zionist Movement’s demand to include the Golan within the future borders, as arises from the official discussions about the future of the Land of Israel.

In 1917, against the backdrop of the Balfour Declaration, the Zionist Movement began promoting proposals for the borders of the future Jewish State. In the book “Land of Israel,” which was published in 1918, David Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (future Israel’s second president( presented the desired borders of the Jewish State, and emphasized economic and strategic rationale with the aim of ensuring the establishment of a “strong and modern state.”

After World War I, the attempts to renew and expand the Jewish population in the Golan and the Hauran were resumed. The leadership of the Zionist Movement made this matter a top priority. Delegations on behalf of the Gdud Ha’Avoda (the Labor Brigade) and Yosef Trumpeldor, members of HaShomer (the Guard – Jewish defense organization in the Land of Israel) and the Ahdut Ha’Avoda (Labor Unity) Movement toured the region in order to assess the means that were needed. Concurrently, Chaim Weizmann, the President of the Zionist Organization, also continued lobbying towards this objective in international diplomatic channels.

In 1919, the Zionist Movement submitted a memorandum about the borders on its behalf to the Versailles Peace Conference, which included a demand that the northern border of the future Jewish State also encompass the Golan Heights. The Zionist Movement’s proposed northern borderline ran slightly south of the city of Sidon in an easterly direction, turned southward along the line separating the eastern and western slopes of Mount Hermon and continued from there parallel to the route of the Hejaz railroad tracks. This demand relied, in addition to its historic context, on economic and geographic rationale that resulted, inter alia, from surveys that the Zionist Movement had commissioned from British firms with regard to the economic future of the Land of Israel. Subsequently, the Zionist Movement worked feverishly in diplomatic corridors opposite France, the United Kingdom and the United States, in order to achieve recognition of these borders of the future Jewish State.

During the conference, the United States recognized the borders demanded by the Zionist Movement. The United States also stressed the need for returning the Jews to the Land of Israel within borders that will guarantee that the Jewish State has control over its sources of water on Mount Hermon. The Americans agreed with the Zionist Movement that the viability of the new State is contingent upon the feasibility of agricultural development. In the end, the United States’ proposal was not discussed, because it withdrew from the discussions.

The Zionist Movement’s fundamental position, whereby the Golan is part of the future Jewish State, remained steadfast and unwavering, even after the British-French accords were reached during the 1920s that excluded the territories of the Golan from the scope of British control. During the subsequent years, the attempts to purchase lands in the Golan continued. In 1934, the company Chevrat Hachsharat HaYishuv, under the auspices of Yehoshua Hankin, purchased about 300 square kilometers of land in Betiha and in the Golan, northeast of the Sea of Galilee, with the aim of creating a continuum of Jewish communities with the Hauran region. The project failed as soon as the local Arab leadership discovered that the Zionist Movement was behind the purchase.

In 1938, the Woodhead Commission arrived in the Land of Israel for the purpose of examining the feasibility of carrying out the conclusions of the Peel Commission regarding the partitioning of the land and severance of the Jewish Yishuv (Jewish residents in the Land of Israel) from the northern sections of the Upper Galilee region. The Jewish Agency submitted a memorandum to the Commission and emphasized the importance of the Golan and its being part of the Land of Israel:

“The area between the northern border of the Land of Israel and the Litani River, and between the territory of the Golan, bordered in the south by the Yarmouk and in the west by the Jordan, has always been considered part of the historic Land of Israel.”

Between 1934 and 1944, several courses of action and efforts were made to re-establish Jewish communities in the Hauran. These courses of action failed, inter alia, due to disagreements among the institutions of the Jewish Yishuv in the Land of Israel.

In 1944, the French Mandate over French Syria ended and the region was handed over to independent Syrian control. Despite the validity of Jewish proprietary rights to lands in the Hauran, and the fact that these rights were lawfully and legally arranged by PICA even after the end of the French Mandate, Syria rushed to expropriate the ownership over these lands and nationalized them, inter alia, by claiming that at issue are sacred lands (Waqf). The Jewish Yishuv in the Land of Israel did not reconcile itself to the nationalization of the lands in the Hauran and tried to defend the Jewish ownership through litigation in a court in Syria, but to no avail.

Establishment of the State of Israel

The acceptance of the partition scheme on the eve of the establishment of the State of Israel did not change David Ben-Gurion’s view concerning the territories that were torn from the Land of Israel or his aspiration to return and restore the historic settlement in them. These views received firm expression during a speech that he gave to the Mapai Council (acronym for Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael, the Workers’ Party of the Land of Israel) in Tel-Aviv in August 1947:

“[…] We demand that the Jewish community shall encompass the western part of the Land of Israel and not just Transjordan of today, but also the Hauran and the Bashan and the Golan up to south of Damascus.”

On the eve of the U.N. vote on November 29, 1947, there were 14 Jewish communities at the foot of the Golan. The establishment of Jewish communities in the Golan Heights was resumed only in 1968, after the Six-Day War, and is continuing to this day. To this day, the Keren Kayemet leIsrael (Jewish National Fund) owns the proprietary rights to many plots of land in the Golan and in the Hauran (it received them from PICA after it dissolved) – lands that were purchased with Jewish money for settlement purposes.

Apparently, ever since the discussions held after the Six-Day War concerning Syria’s demands for sovereignty over the Golan Heights, and to this day, the State of Israel has never officially insisted on claims of a right to the Jewish lands in the Hauran and has not raised any possibility of an arrangement that would include a waiver of proprietary rights to lands in the Hauran in exchange for recognition of its rights to lands in the Golan.